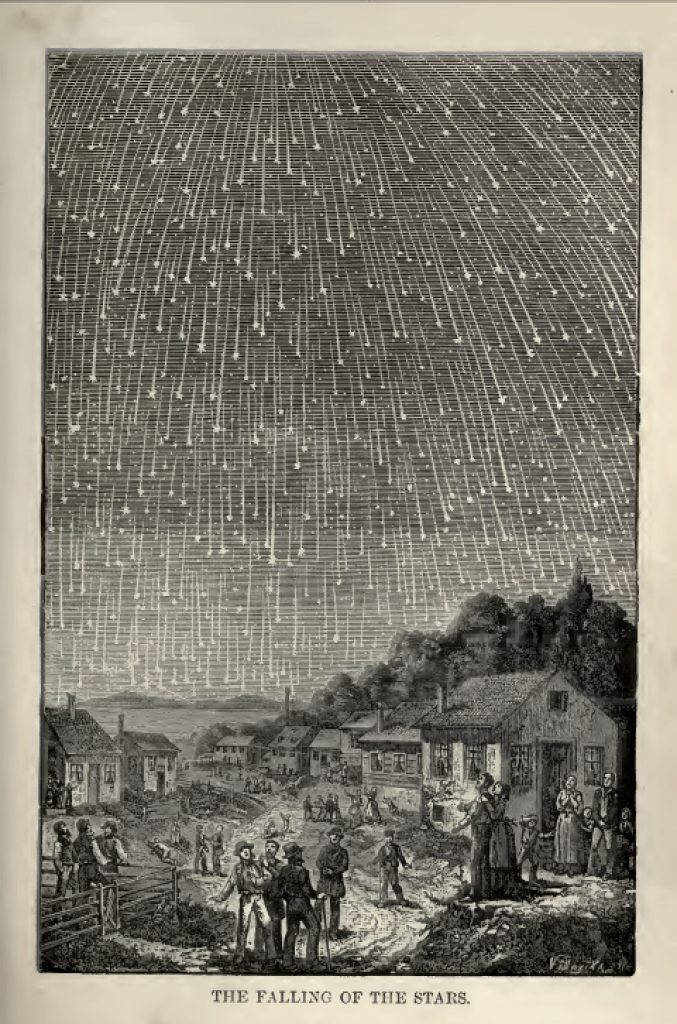

Last night marked the peak of the annual Geminid meteor shower, a light show courtesy of 3200 Phaethon, which has the orbit of a comet and the rock fraction of an asteroid and passes, at its closest approach, only 20 million kilometers (13 million miles) from the Sun (much closer than the planet Mercury). In the last few days I’ve seen lots of posts and tweets drawing attention to the event and how to best view it, and a couple of them were accompanied by this very striking image:

That looks pretty spectacular! Intrigued, I did a little digging on the origins of the image and came across this article by David W. Hughes, in which the author calls it “the world’s most famous meteor shower picture.”

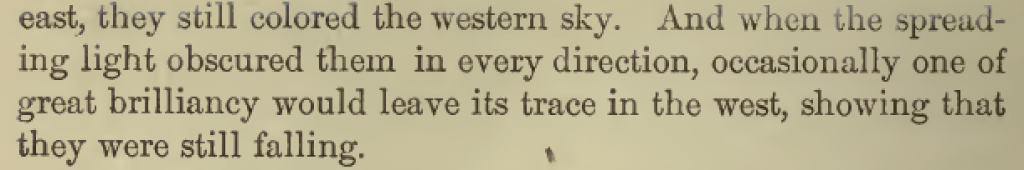

It’s a woodcut depicting the Leonid meteor shower (not the Geminids) on November 13, 1833, based on an eyewitness account given by Joseph Harvey Waggoner fifty-four years later. Having observed the event at the age of 13, Waggoner always remembered it as a moment of significance: “To nothing do I look back with greater delight, and I never think of it without feelings of thankfulness that I was permitted to behold it.” As an adult, he converted to the Seventh-day Adventist faith and became convinced that the 1833 meteor shower was the very same “falling of the stars” mentioned in the gospel of Mark as a sign of the return of the Savior (Mark 13:25). He approached the Swiss artist Karl Jauslin to commission a drawing for him, and Adolf Völmy engraved the woodcut, which was circulated in the Adventist publication The Signs of the Times and later appeared in Bible Readings for the Home.

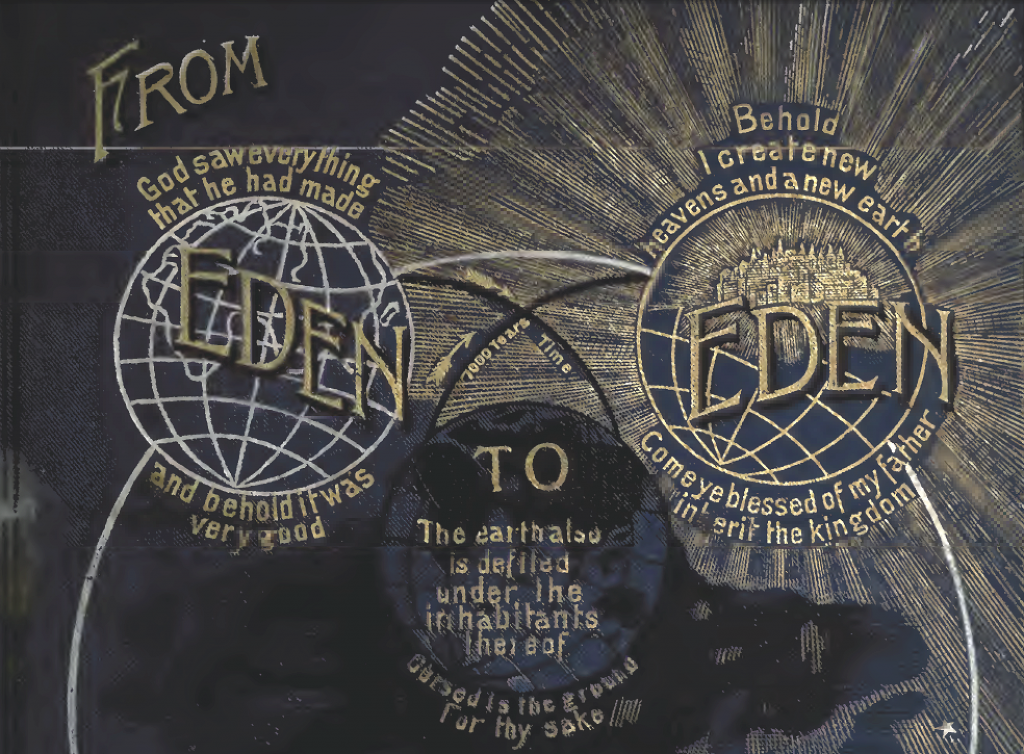

Waggoner published a book himself in 1888 called From Eden to Eden: A historic and prophetic study, a companion to “some of the most interesting portions of the Scriptures.” Chapter 18 is devoted to “Signs of the Second Coming of Christ,” and the meteor shower features prominently: “This was the last of the three signs given by our Saviour, and was altogether the most glorious and magnificent in its fulfillment, which was November 13, 1833.”

While the woodcut may seem exaggerated, contemporary accounts (some compiled in Hughes and others in Mark Littman’s The Heavens on Fire) seem to bear out Waggoner’s awed recollection of the event, both in the number of meteors observed and in their radiant pattern. In his own words:

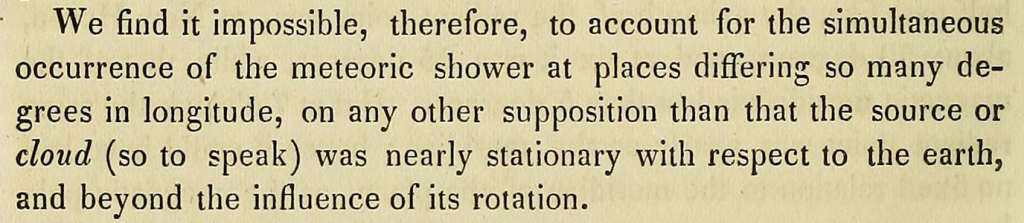

The origin of the meteors was unknown, but this display made it it clear to Waggoner and others that they were not atmospheric phenomena. As the noted astronomer Denison Olmsted put it: “This is no longer regarded as a terrestrial, but a celestial, phenomenon; and shooting stars are now to be no more viewed as casual productions of the upper regions of the atmosphere, but as visitants from other worlds, or other planetary voids.” Inspired to collect information about the meteor shower, Olmsted presented his observations in two papers in The American Journal of Science and Arts, concluding that the meteors must have originated as a cloud of particles outside the atmosphere of the earth:

An astronomer by the name of Hubert A. Newton contributed to this hypothesis by cataloguing other observations of meteor showers that seemed to occur at the same time of year, going back as far as A.D. 902 (recorded in Latin and Arabic sources). From this data, he suggested a recurrence period of 33.25 years and predicted that the next big event would occur in 1866. He was right! And just a couple of months later, two independent astronomers (with fortuitously alliterative names) discovered comet Tempel-Tuttle, which has a period of 33.22 years (modern value). Several observers pointed out the similarity between the orbit of the comet and the periodicity of the Leonids (described here).

An astronomer by the name of Hubert A. Newton contributed to this hypothesis by cataloguing other observations of meteor showers that seemed to occur at the same time of year, going back as far as A.D. 902 (recorded in Latin and Arabic sources). From this data, he suggested a recurrence period of 33.25 years and predicted that the next big event would occur in 1866. He was right! And just a couple of months later, two independent astronomers (with fortuitously alliterative names) discovered comet Tempel-Tuttle, which has a period of 33.22 years (modern value). Several observers pointed out the similarity between the orbit of the comet and the periodicity of the Leonids (described here).

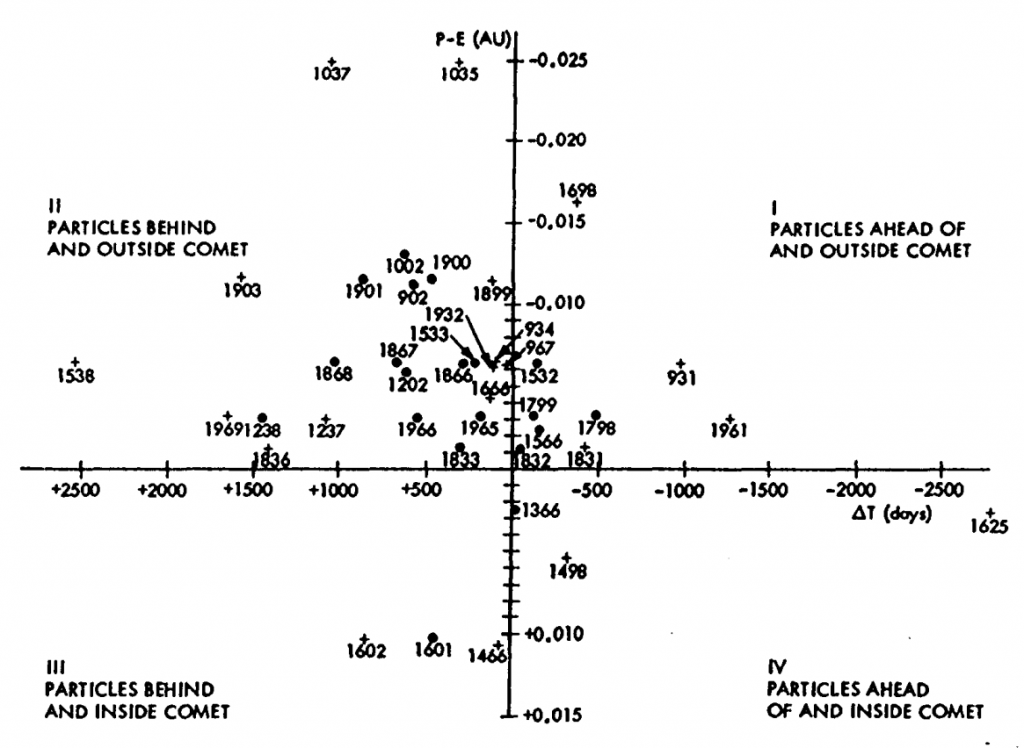

The relationship between Tempel-Tuttle and the Leonids remained obscured, however, by the variability of the meteor rates from year to year. Some time later, in 1981, an astronomer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Donald K. Yeomans, addressed this variability by mapping out the dust distribution surrounding the comet and its spatial relationship with Earth during closest approach.

One result of Yeomans’ work: the dense dust around the comet lies mostly behind and outside of its orbit, suggesting that the solar wind and planetary perturbations control its distribution!

None of this has anything to do with the Geminids in particular, which are caused by a different orbiting body (3200 Phaethon), but I’ve found it pretty interesting, so here’s to meteor showers!