I chose this topic (post-glacial rebound) because it combines a lot of subjects that I really enjoy learning about – orbital cycles, glaciers, geophysics, etc. It has nothing to do with my own research (in science or history of science), but I thought it would make for a good short video. I also just think it’s so cool that the Earth is still adjusting to the retreat of the ice sheets – it’s one of the reasons I went into planetary science in the first place! I drew all of the images in the video, but I based them on several source figures that I’ve included here. If you liked the video, I’d also highly recommend that you read Richard Alley’s Two-Mile Time Machine.

Transcript:

Rebound (An Earth Story)

Once upon a time – only a moment ago, really, in the grand scheme of things – the Earth was a very different place. Her continents were covered with ice sheets thick that scoured the landscape into new and fantastic landforms, and ocean levels were low, with all that water locked up in ice.

This was the last glacial maximum.

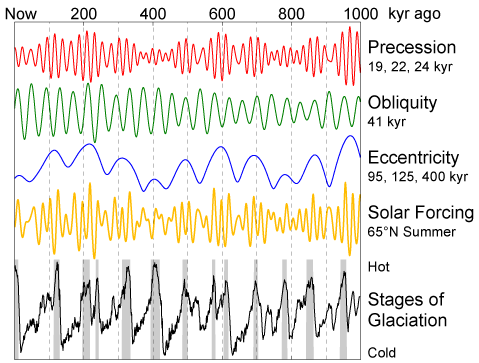

It had happened before – several times, all throughout the current Ice Age, which began 2.6 million years ago. Tugged by unseen forces, Earth constantly squirms in her orbit, shifting the tilt of her spin axis and nudging the shape and orientation of her elliptical path. All of these changes happen at their own assigned frequencies, and they all add up to pattern of more and less light received from the Sun, more and less intense seasons.

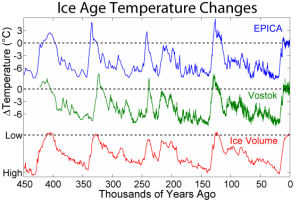

When temperatures are low enough, more ice accumulates during the winter than melts during the summer, and permanent ice sheets can grow. This temperature record is written right into the ice. The annual layers of deposited snow capture different amounts of oxygen-18 – a much less abundant, heavier cousin of typical oxygen-16 – and that depends on the temperature. We can measure these differences in ice cores and reconstruct hundreds of thousands of years of climate history.

Ice – kilometers of it – weighs a lot, and the continents bent under the load, which was too large and too widespread to be supported by the rigid lithosphere alone. Instead, the land subsided under the ice sheets, and Earth’s mantle shuffled out of the way to accommodate the extra weight. Rocks are solid – even at great depth – but with enough time and under pressure, they will deform and even flow, just like a fluid, but on a much longer timescale.

The ice had been building up for tens of thousands of years – plenty of time for Earth to adjust – and, like an iceberg floating in water, the continental glaciers depressed the landscape just enough to compensate for their added mass.

But all of that was about to change.

The retreat of the glaciers happened much faster than their accumulation – too fast for Earth to react in real time. When all that ice suddenly disappeared, it threw everything out of equilibrium again. First there was an immediate response. Some of the stress from the weight of the ice had been stored elastically in the rock, and as soon as it was removed, the land bounced back like a tennis ball. But that was only part of it. The viscous mantle takes a longer time to respond to sudden changes – in fact, it’s been slowly adjusting ever since, and it still has 10,000 years to go! This post-glacial rebound (or glacial isostatic adjustment) is causing parts of Canada and Scandinavia to rise by about a centimeter per year, and by measuring these movements, we gain important information about the material properties of Earth’s mantle! It’s hard to run a planet-sized experiment, so when it happens naturally, everybody wins!

Now THAT is a huge (stress) relief!

A couple more links:

- The ‘glacial features’ drawing was drawn based on this image.

- I created the background by modifying this one, free from Church Media Design.

- The music is “Make It Easy” (licensed from PremiumBeat.com, by user Rimsky)

Finally, I want to thank a few people for watching an early draft and making some really insightful comments: Jon Wolfe, Crystal Dilworth, Laurence Yeung, Jorge Cham, Matt Siegler, and Ben Sveinbjornsson – thanks, guys!